How do you get thousands of small farmers to save the Amazon rainforest when it could mean they have to buck tradition or adopt unfamiliar methods? What if they’re multigenerational cattle farmers who’ve never heard of carbon credits? Skoog has a plan.

The company, led by Augusto Andrade (co-founder and CEO) and Nima Darabi (co-founder and chief product and technology officer), makes it easier for landowners to profit from carbon markets.

Skoog’s employees talk to farmers, universities, and agricultural associations across Brazil. They educate landowners about how they can make more money by preserving forests and improving agricultural practices than by cutting down trees.

Skoog’s software will show landowners alternatives to deforestation and how much they can earn from them.

Eduardo: How did you get started with your work in the Amazon, and how did you end up here?

Augusto: I’m originally from Brazil. My parents are farmers, and my dad’s an agricultural engineer. I studied engineering and had a career in consulting. I traveled and moved around a lot. After 15 years, I took a break to do a start-up program in Norway. That’s where I met Nima and it all came together. His story and his passion for nature inspired me.

Nima: I was originally a caged animal in Tehran, a concrete metropolis. My passion for plants came from not having the good fortune to grow up around too many of them. Now I live in Norway, where people live in close contact with nature. I became fascinated with plants.

At first, it was just curiosity. Then I thought about the potential impact. I decided we should use our resources to change our systems. Now I come up with economically viable ideas to show to investors.

When I pitched my idea about how urban trees can affect property prices, Augusto said, “Hey, you can use this in the carbon market.”

Our mission from the start has been to grow the economy and GDP at the same time we preserve nature. Skog means forest in Norwegian. We added an “o” so foreigners can pronounce it more like how it sounds.

Put a price on keeping or planting trees

Eduardo: How does it work?

Augusto: We put a monetary value on forests. As Nima says, trees are data friendly because they don’t move. You can count them from the sky.

Our first application is related to decarbonization and carbon financing. We work with private landowners, mostly in Brazil. Half of Brazil is privately owned. Landowners think the best way to use their land is to raise cattle or plant soybeans. We assign a value to that—or to not doing that.

We ask how much carbon they would emit by deforesting versus reforesting an area. We give landowners access to carbon markets, so they can consider using their land differently.

They can get a financial return, without deforesting their land or using it in other harmful ways.

Eduardo: You said carbon financing is the first step. What are Skoog’s long-term goals?

Show tree growth with virtual reality

Augusto: To understand how much carbon an area can sequester, you need to know what trees are there. Then you can use them sustainably.

For example, acai, a fruit that grows on trees in the Amazon, is worth a lot because it’s gone mainstream.

The same technology we’re developing to count and classify trees, we hope to use to understand the value of the fruit trees and exploit them sustainably.

Eduardo: How do you get the data you need to assess on the platform?

Augusto: From several different sources, including public records. We combine that with carbon mapping to understand how much carbon is in different areas.

Brazil is a large country with six biomes. Each biome has a different carbon density and faces different risks of deforestation. At first we use a lot of satellite images and carbon maps with relatively low spatial resolution. When we get closer to the final project, we need more granular data, which comes from manual measurements.

We use the cheapest and quickest data-gathering methods that give us confidence to develop the projects.

Eduardo: I read that Skoog can predict financial gains by running four different financial models. What does that mean, and how does it benefit the landowner?

Augusto: Funny story. I was in Brazil, on my farm. I asked my dad, “Why do you raise cattle?”

He said, “It’s tradition. Your grandfather did it and your great-grandfather before that.”

There’s a lot of eucalyptus in the area. Nestlé just reforested a large area with it. I asked him, “Would you be better off financially planting eucalyptus?”

He didn’t know. People have no idea how much their land could be worth if they used it differently. We show them various sustainable scenarios.

It’s like for farming.

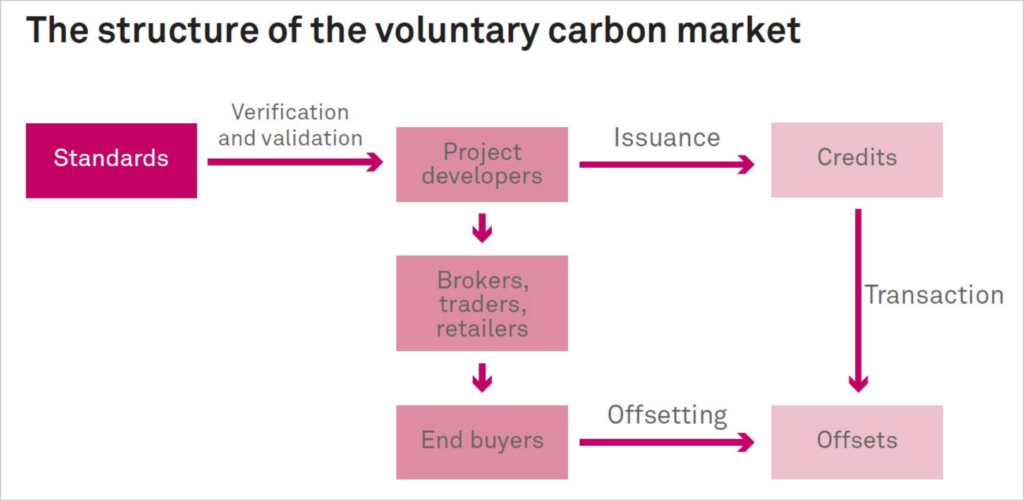

Nima: We have two important tasks: measuring biomass and estimating risk. Each task demands a variety of datasets. We work with the entire process of issuing carbon credits— including verification and sales—from the supply side to the demand side.

Most of the tech companies in this field are attempting to innovate in remote sensing. They use data from airborne and terrestrial LiDAR scans. Those technologies are relatively accurate for estimating biomass.

We also want to capture a view of the trees from above and then use allometric equations to estimate species, biodiversity, and biomass.

Data gathering for carbon markets can be controversial. There are various risk metrics—like —to assess whether a project is likely to produce real results.

Augusto: A lot of tech companies are getting into carbon markets, and more traditional companies are developing carbon projects. We’re trying to combine those two roles. So far, that means me traveling around Brazil. I went to the Cerrado in the Southeast of the Amazon region, which is the second biggest biome. And then I went to the Atlantic Forest along the coast.

I talked to people to test my assumptions and to validate the model. What I suspected was true. Carbon credits are an abstract concept to forest owners. They’ve never heard of them, even though they’ve been around for 25 years.

We want to get the word out to landowners to use their land differently. They’re hard to convince because they’re set in their ways.

So we hold out a carrot—the financial gain they can achieve. Then we show them the damage they’re doing.

When they see the area they’ve cleared and how it looked 25 years ago, they’re shocked.

When they focus on their own piece of land, they forget about the bigger picture—the missing trees, the river that’s drying out.

I talked to cattle ranching associations, cooperatives, and universities. No one has unified them to bring about the changes that are needed.

Eduardo: In systems thinking, we call that a bounded rationality. People make the best decision they can in the moment, but their thinking is limited. When thinking expands, behavior changes.

What’s the process to get in just the voluntary market? How is Skoog changing that?

Augusto: Typically, companies scout for land in areas of high deforestation. They buy up the land, develop and certify the project, and sell the credits.

It’s not very democratic. We’d like the landowner to make money from their property and do good for the environment without having to sell.

We want to connect the buyers and sellers of carbon credits, so that more money goes to the landowners.

We talked to some landowners in Colombia. They’re getting only about a fifth of what carbon credits are worth to them.

Augusto: The more money we can channel to landowners, the more we can compete with things like cattle or soy.

Nima: Regarding the pricing of carbon, it’s a matter of supply and demand in a free market.

Augusto has helped me understand that this market is under supplied. There’s a lot of demand for all these different types of carbon credits, all of which have different pricing. We’re figuring out exactly what factors define the price.

Cryptocurrencies are an interesting example. Ten to 15 years ago, you couldn’t imagine that you could create a currency and establish it as something you can trade with.

We want to register and certify as much as we can to deliver real impact. We want to connect the landowner with the buyer who will pay them not to cut down a forest. We want to facilitate that agreement.

First, we need to identify the agent of deforestation. Whatever source pays them to clear trees for soy or cattle or palm trees, we have to match that.

But we also need to reduce the initial cost. Defining and certifying a project is expensive. For land holdings of less than about 1,000 hectares, it’s not worthwhile for landowners to sell their carbon. We can reduce that threshold to 50 hectares.

Get the word out to farmers, industry associations, and influencers

Eduardo: From the process you described, it seems the biggest bottleneck is getting the idea into the minds of people that they can do something other than what they’re doing now. It’s a matter of diffusing this knowledge.

Augusto: I’ll tell you what they told me on the ground:

“Once someone in the region starts to get paid, things will spread like wildfire. It’s a bad metaphor, I know.”

But the power of word of mouth is why we believe in the boots-on-the-ground method. One of our flagship projects might be with the leader of a cattle association. He can change things by swimming against the tide. Suppose he goes in front of people who make their living raising cattle, and says, “I’m gonna start using my land differently.” That’s real influence.

Eduardo: The theory of diffusion of innovation recognizes that pattern. You enlist change agents. Effective change agents have certain characteristics: They are more open and usually more educated than most of the population you want to influence. They have more resources, so they’re more receptive to change. Their influence spreads outward through the concentric circles of their social connections.

Augusto: You’re right. I’ve worked in business transformation for 15 years. If you’re coming in and telling people to change their processes and systems, you need to have influencers everywhere.

Eduardo: How long is the process, from identifying an opportunity to actually getting the carbon financing?

Augusto: It takes one to two years, from finding the land to developing and certifying the project. We want to shorten that time to about three months. We don’t have time to waste.

Regenerative agriculture practices

Eduardo: There’s a lot of deforested land for growing cattle. Brazilian steaks are very popular. What can be done to minimize impact with land that’s already being used for cattle?

Augusto: There’s rotational grazing. My father, an agricultural engineer, does that. It’s a longer-term strategy. Let’s say he has a big area that he’s subdivided. He never lets the grass get shorter than a certain level.

If there are too many cows grazing, they eat more and the grass gets shorter. When it rains, it washes away some of the soil. You don’t want that. So he rotates them.

You can also cultivate a super pasture, a mix of forest and pasture. Branches fall, leaves fall, and that becomes organic matter. That’s why in our logo there’s an infinite loop. Things just…

Eduardo: Regenerate.

Augusto: Yes. But they need an incentive to do it. Some of this stuff is not easy to implement.

The president of a cattle association tried doing it himself, and he failed. You need the right combination of grass and trees. The topography matters. The distance between the trees matters. I think he got too much shade on the pasture.

But when it works, it really works. It’s synergistic. The trees grow better than they would without the grass. And the grass grows better than it would without the trees. It gets more productive, so the cattle grow faster. It’s a win-win. But you need knowledge. That part is hard to scale.

Nima: Even when people clear-cut forests, it’s much better if they leave that last 2% of trees. The cow still has plenty of grass to eat, is well fed, fatter and happier.

We humans extract everything from nature. The modern mindset of clearing and optimizing and extracting for maximum value is not productive. We push extraction to the extreme. But just leaving that little bit, or bringing it back, can lead to magic sometimes.

As I’ve tried to make trees profitable in the past four years, I’ve heard from many people about manifesting the change you want. We use and to help visualize change.

Trees are not difficult to visually augment. AR and VR help show people: This is your empty land. This is what it will look like if you plant these species, in three years and in five.

When people see it, they’ll pay for it. It’s much easier to persuade them. So we’re looking into using AR and VR for that.

Eduardo: When landowners go through the process and get approval for carbon financing, what’s next? What other activities can they pursue? Augusto: That’s a good question.

“People think landowners will be paid to do nothing. Actually, they’ve been providing a service for free.”

In Brazil, you must preserve a large portion of the Amazon land on your farm. You can clear only 20% of the trees on that land. You must manage the remaining 80% of forest land.

You have to maintain a fence around it, and you have to monitor it. You must manage fires. So landowners will continue to preserve the portion that remains forested, and they’ll be paid to do so.

That’s at the farm level. Zooming out, we’re looking for areas where we can close gaps that reduce biodiversity. Say you have some farms and reserves here and there, with deforested land in between them. Biodiversity is locked away in these isolated plots. We see where we can close these gaps by making the reforested areas much larger. We prioritize such opportunities.

Farmers will still farm. But they’ll do it with a collective way of thinking that preserves more land.

There are also social benefits. We’re thinking about establishing agro-forestry schools in the region.

It will be an entire new ecosystem, with more companies doing forest measurement, reforestation, and biodiversity studies. They’ll implement those systems where they are sustainable. The process will create cool jobs for the next generations.

Young people are less inclined to farm today—at least the way farming is currently done. They’re becoming influencers and YouTubers.

Carbon is just one part of the wildlife economy. Non-timber forestry products, like native fruits, could bring a return to .

A guy in Brazil came up with an idea for an ice cream shop with a hundred flavors you’ve never heard of. He has indigenous communities gathering fruits in the forest, and then he turns the fruits into ice cream.

Then there’s ecotourism. People will pay to come and see a thriving rainforest.

There are so many different things they do with their land, other than harvesting trees. Land will be more profitable, and owners will be happier. And the environment will win.

Eduardo: When will we see this live? Where are you finalizing the platform and getting it out there?

Nima: We’ll be able to ship our first in November.

Augusto: We’re developing projects in parallel with building the technology so we can create some case studies. We are already generating some conservation and restoration projects.

We already have partners for those. I visited a guy who has reforested 3,000 hectares in the Amazon, using a proven method. He supplies the seedlings and the people to do the reforestation work.

Eduardo: Before we finish up, what leader do you look up to?

Nima: George Monbiot. A writer and environmental activist who has brought important ideas into the mainstream.

Eduardo: Do you think we’ll make it through the challenges of climate change?

Nima: Yes, if we do it slow and steady, like nature does.

Augusto: Yes. You need to be resilient and do the work. There’ll be ups and downs. Sometimes you wake up thinking, What am I doing with my life? And sometimes you think, let’s go change the world.